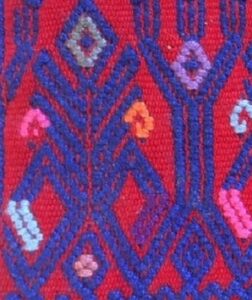

Maya women have been weavers for as long as their people can remember. Weavers say that Moon taught women to weave sacred designs. Maya legends, describing how female saints gave communities their distinct designs, emerged as early as the 1500s when the Spanish invaded South and Central America. Today weavers encode in their creations a deeply held belief that people, plants, animals, Earth, and other spiritual beings must cooperate to keep the world in flower. Maya weavers still turn to spiritual guides as well as to each other for help in weaving and in supporting their families and communities. Weavings are made on a back-strap loom using a process called brocade to create designs as they weave. Women weave their own and their daughters’ clothing and tunics for their kinsmen. Although men often wear non-traditional clothing, they proudly wear their traditional garments to show respect for their ancestral ways and solidarity with fellow villagers.

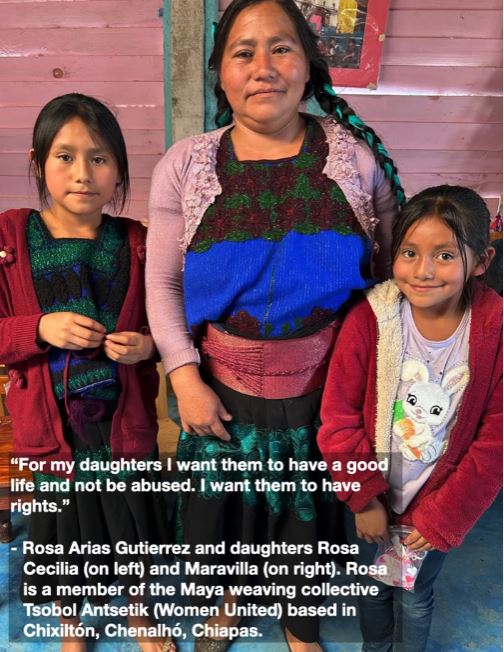

Despite the strength of traditions such as weaving, strident economic inequalities in Mexico have created intolerable conditions for indigenous people in Chiapas. Hunger and disease, high child mortality, scarce and distant water supplies, and minimal or non-existent health and educational facilities are the legacy of the unjust economic system in Chiapas. Weaving products to sell through fair trade markets provides women a means to support their families while staying on their lands and remaining part of their families and communities.

Nevertheless, for decades people have had to migrate to find work to supplement their subsistence farming. Migration has also intensified in recent years in response to escalating violence in the state fueled by a combination of ancestral conflicts and the encroachment of drug cartels and paramilitary groups seeking to extend their control. In the face of government inaction, paramilitaries, hired killers, self-defense groups and private security agencies have been multiplying throughout the state. The effects of this reign of terror include displacements of large numbers of people from their lands; assassinations and disappearances of community leaders; the forced recruitment of young people into criminal gangs; and a tenor of terror which tears at the social, economic, and cultural fabric of communities.

Learn more about weaving in highland Chiapas:

Morris, Walter F. Jr. 1987 Living Maya. New York: Harry N. Abrams

_____2011. With Alfredo Martínez, Janet Schwartz, and Carol Karasik. Guía textile de los altos de Chiapas/A Textile Guide to the Highlands of Chiapas. Loveland, CO: Thrums.

_____ 2015 With Carol Karasik and Janet Schwartz. Maya Threads: A Woven History of Chiapas. Loveland, CO: Thrums.

Simonelli, Jeanne et al. ed. 2015 Artisans and Advocacy in the Global Market: Walking the Heart Path. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Tsobol Antetik. 2017. Our Clothing/K’utik/Nuestra ropa.

To keep informed about conditions in Chiapas we urge you to go to the following websites:

Center for Human Rights Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas(https://frayba.org.mx) .

Schools for Chiapas (https://schoolsforchiapas.org;

Las Abejas (www.acteal.org);

The EZLN (www.ezln.org.mx and www.enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx).